The desert is empty, khaki and rolling. Then there is a gazelle, sprinting through the dream. The crack of what we instantly recognize as gunfire, a Toyota pickup with a half-dozen men riding in its bed are firing on the animal. They raise their AK-47s. They miss, they miss, the animal vanishes.

But ebony idols do not run. We receive them as typical African wooden statues, the sort of ornamental figures that end up in places like Pier 1 Imports. Bullets whack into them, biting off chunks of wood, causing them to jump in the sand. A tendril of smoke curls to heaven.

Timbuktu

90 Cast: Ibrahim Ahmed, Toulou Kiki, Abel Jafri, Fatoumata Diawara

Director: Abderrahmane Sissako

Rating: PG-13

Running time: 97 minutes

This is not the most efficient way to destroy what is idolatrous. This is how thugs recreate, taking potshots at what is beautiful. At art.

This is one of the major themes of Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako's narrative feature Timbuktu, the divide between the literal-minded vulgarity of oppressors and more generous souls. Needless to say, this does not make it a movie that jumps off the marquee -- most of the people who will see it in the theater this weekend have been waiting for it, some because they feel compelled to see every Oscar-nominated film they can, others because they read reviews of it online or in publications of national scope.

A smaller subset of this audience may have some grasp of the political situation that inspired Sissako -- the three-month occupation of the title city, a relatively small outpost (the current population is around 55,000) on the southern edge of the Sahara in the nation of Mali in West Africa -- by the jihadist group Ansar Dine in 2012. Sissako's jihadists are by and large thugs, moral idiots looking to shut down all opportunities for delight and pleasure. They have banned music and smoking and soccer -- even idly standing outside one's house watching the world turn is forbidden. Women must cover themselves, they must wear socks and woolen gloves. When a fishmonger complains that she can't do her work in these gloves, she's arrested.

Yet while they rule through terror, they are not subhuman, and the people they seek to subjugate are not simple.

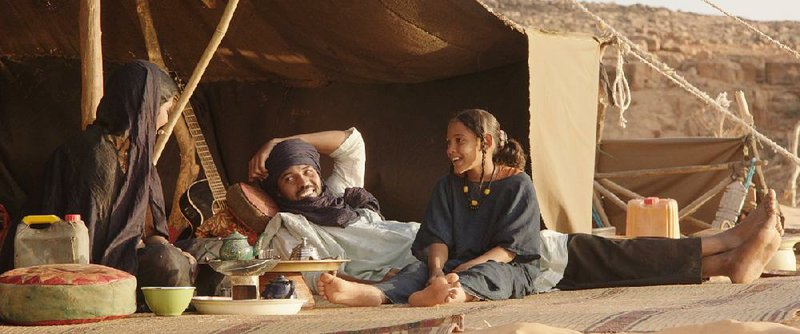

Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed) and his wife Satima (Toulou Kiki) live a seemingly idyllic existence in a tent on the outskirts of the city with their daughter, Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed), and adopted son, Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed). They subsist by keeping a tiny herd of cattle, led by their favorite cow, GPS. They are Muslim, but not strident. Kidane is a musician, and according to Issan, not so great a herdsman. While their neighbors have moved, he sees no reason to -- the neighbors will eventually come back, all this will pass.

One of the leaders of the jihadists, a middle-age man named Abdelkerim (Abel Jafri) is obviously smitten with Satima -- he seems bashful in her presence, even as he orders her to cover her face. While she says he scares her, we sense that he's more than a little envious of her life. We might think we know what is going to happen here, but Sissako confounds our expectations. It is Kidane who commits an atrocity after a local fisherman kills his beloved GPS. Sissako marks the moment with a stunning long widescreen shot, with Kidane wading through the fisherman's small pond, trailing a long-tailed wake as the sun sets in the hills beyond.

In another stunning sequence, young men pantomine a ball-less soccer match -- apparently an allowed activity -- as a pair of jihadists thread past them on a motorbike, their weapons slung and ready. And then there's Fatou (Fatoumata Diawara), condemned to 80 lashes (40 for playing music in her home and another 40 for being in the presence of her male accompanist), singing through tears as the whip comes down.

Like his mentor, Palestinian director Elia Suleiman, Sissako injects tenderness into what otherwise might be relentlessly depressing scenarios, but unlike Suleiman his primary tactic is not satire. Sissako is an artist of intellectual rigor who builds from tight specifics and subtlety a damning case against the impulse to bully under cover of piety. He has made a movie that might confound the vulgar literalism of religious censors, a critique of the lack of imagination inherent in every fundamentalist movement.

While it's unlikely to make much of a dent in the national consciousness, it is a better distillation of the cultural struggle between freedom of expression and the urge to repress than any documentary collage of talking heads and archival footage could ever be. Timbuktu is a song of fury, a lyrical and forceful indictment of the enemies of joy.

MovieStyle on 03/20/2015