If Arkansas is unable to execute seven death-row inmates as scheduled by the end of the month, its expiring supply of midazolam -- one of three drugs used in lethal injections -- will still be good, a clinical pharmacologist testified Wednesday.

RELATED ARTICLE

http://www.arkansas…">3 state reporters to witness deaths

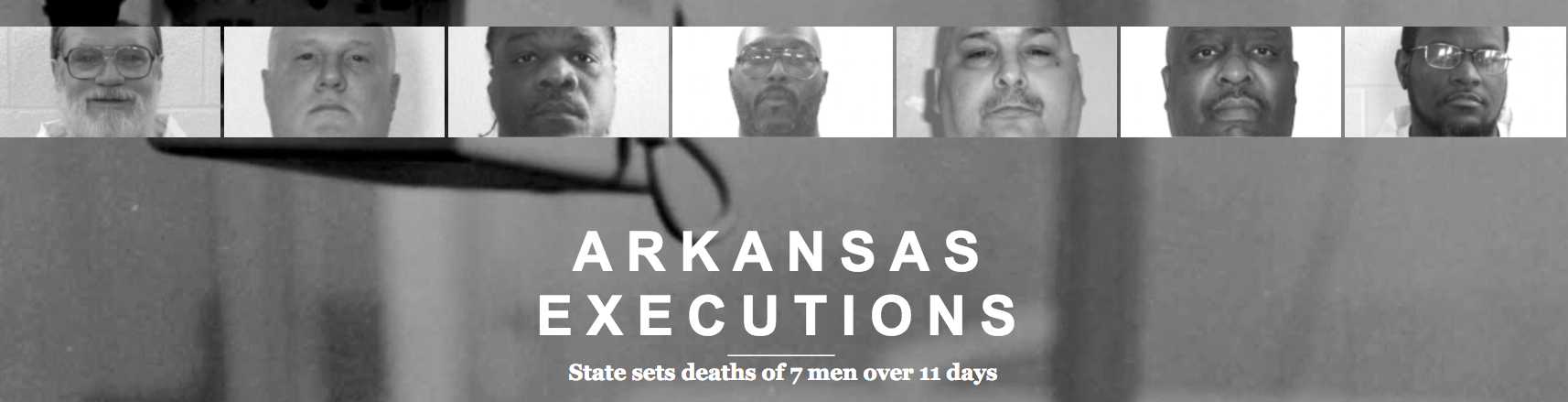

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Daniel Buffington of Tampa, Fla., the first witness to testify for the state in a hearing that began Monday, told U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker that just because the state's bottles of midazolam list an expiration date of April 2017, "it is absolutely inappropriate to assume that the product is somewhat degradate" on May 1.

Attorneys for the condemned men are asking Baker to issue a preliminary injunction preventing the state from carrying out the executions on the compressed time schedule, which Gov. Asa Hutchinson set to beat the expiration date. The attorneys say the fast-paced schedule increases the likelihood of mistakes that could harm the prisoners and prevents them from preparing an adequate defense, in violation of their federal due-process rights.

With the first execution scheduled for Monday night, Baker said the injunction hearing will end by 8:15 p.m. today. She hasn't said whether she will rule from the bench or issue a written ruling, but her practice is to take matters "under advisement" and later issue a written order.

In Wednesday's hearing, Dale Reed, the chief deputy director of the state Department of Correction, revealed to Julie Pitt Vandiver, an assistant federal public defender, that Bruce Earl Ward is scheduled to be executed first on Monday at 7 p.m., followed by the execution of Don Davis at 8:15 p.m. Vandiver, who is representing both men, told Reed that she hadn't been able to find out until then which of her clients is scheduled to die first.

If something should go wrong during Ward's execution, Reed said, the timetable is flexible and the second execution will be carried out later that night.

Later in the day, Vandiver questioned Reed and Rory Glen Griffin, a licensed practical nurse and department employee, about the minute details of preparing for the executions and any unforeseen occurrences.

Baker closed the hearing periodically to allow the employees to answer questions covered by a pre-hearing order that protects the department from revealing aspects of the execution plans that it maintains are confidential. A reporter from KTHV-TV submitted a written request for "unrestricted access" to testimony of department officials, citing both the state and federal Freedom of Information acts, but Baker denied the request, saying federal court proceedings aren't subject to the state Freedom of Information Act and that the federal law doesn't cover the courts.

Buffington, who is on the faculty of the University of South Florida at Tampa, testified Wednesday that most drugs can be used four to five years past their expiration dates, which is when they fall to 90 percent of their potency. He said the FDA requires manufacturers to list a month and year through which "they can say with full confidence" that the medication is as potent as ever, but as long as the medication remains in its commercial packaging, there is "no danger" of it being less effective when the month ends.

There "would be no necessity" to test the drug after the expiration date, Buffington said. He noted that the FDA requires all drugs to be tested for potency and purity before they are sold.

He said midazolam "does have cases of paradoxical reaction," a rare condition in which a drug has the opposite effect than for what it is intended, but in the case of midazolam, "it would be stimulation instead of sedation." If that occurred during an execution, he said, the prisoner wouldn't pass the "consciousness test" that the execution team is required to perform before administering the second and third drugs -- a paralytic and a heart-stopping drug -- and the procedure would be terminated. He said he is unaware of any prisoner anywhere suffering a paradoxical reaction to midazolam, though the drug does cause "adverse reactions" such as respiratory depression when a large dose is administered rapidly, as in an execution, and hiccuping and coughing, which are common in executions.

Botched executions elsewhere in the country in which midazolam was used weren't caused by the drug, he said, but by the improper administration of it. He said there have been 10 to 20 executions carried out in Florida using the same three-drug cocktail as Arkansas uses, with "no medication-related concerns."

Disputing another pharmacologist who testified a day earlier on behalf of the inmates, Buffington said, "Midazolam is an appropriate selection as a first agent ... to obtain appropriate levels of sedation and anesthesia. ... We have not demonstrated a ceiling effect in humans -- only in clinical theoretical data."

Pharmacologist Craig Stevens of Oklahoma had acknowledged on Tuesday that the "ceiling effect," the point at which the drug stops producing an anesthetic effect despite higher doses, had been proved only in "in-vitro" studies, but said the drug is too dangerous to be tested at high doses on human beings. Stevens also said that midazolam is intended to be used as a calming agent before the administration of stronger, true anesthetics. He said it isn't meant to be used by itself for anesthetic purposes, and it isn't likely to block the pain a prisoner may experience when receiving the next two drugs in the protocol.

Buffington, however, testified that 500 mg of the drug, which Arkansas' protocol calls for, is sufficient to render a patient unconscious. He said that at the "levels and depths " that a 500 mg dose would supply, a patient couldn't feel pain.

Any claims that midazolam can be degraded or contaminated after it is prepared for injection are "preposterous," Buffington added.

Baker also heard Wednesday from Larry Norris, who was director of the Department of Correction for 16 years before he retired. He testified that in the executions he oversaw, none of which involved midazolam, the prison had no problem juggling as many as three executions in one night -- though it never carried out a series of executions over an extended period of 11 days, which he acknowledged would be exhausting.

If the schedule for executing the seven inmates were up to him, Norris said, "I would have opted for setting four a day."

He explained that prison officials would be in a "ramped up" mode on that day, giving them the energy and focus to carry out the procedures, but they wouldn't have to deal with other logistics, such as coordinating with the state police, for several days in a row.

"The prison is 24-7, 365," Norris said. "It never slows down. It never stops. When you set an execution at Cummins, it reverberates through the whole system."

Metro on 04/13/2017