"I would have probably said the story was unfilmable," Ted Chiang says.

Chiang is talking about his short story "Story of Your Life," which, despite Chiang's skepticism, became the Oscar-nominated movie Arrival. One of those nominations went to Eric Heisserer, who adapted Chiang's story for the screen.

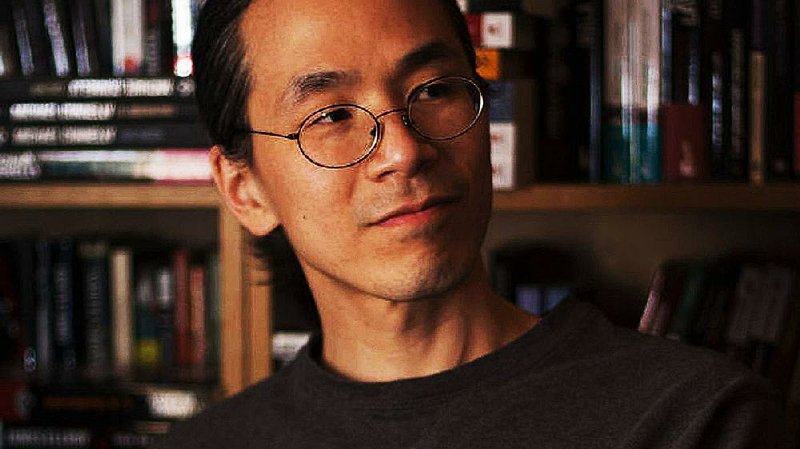

"This is just two people sitting in a room talking," Chiang says from his home in Bellevue, Wash. "That would be a fair description .... Most of what is happening in those stories is happening in someone's head. I don't know how you'd adapt that."

For the sake of Chiang and filmgoers who want science fiction stories that have more to offer than explosions and CGI monsters, it may be a blessing that screenwriter Eric Heisserer (Lights Out) and Canadian director Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Sicario) disagreed about the cinematic potential of Chiang's story.

Arrival has been a box-office hit, and it's still playing theatrically in some markets despite the fact that it has been on Blu-ray since Tuesday. The film has also been nominated for Best Picture at this year's Oscars, and Villeneuve has been nominated for Best Director. It stars Amy Adams as linguist Louise Banks, who has been tasked by the U.S. government to determine how to communicate with space aliens who have landed across the globe.

People Talking Without Speaking

The challenge is formidable because the aliens (dubbed "Abbot and Costello" in the movie and "Raspberry and Flapper" in the story) don't have throats or even the same concept of time and distance that we do.

"I think it's safe to say that any species capable of interstellar travel would necessarily have a different perspective on things than we would because the scale of distances involved is nothing like crossing the ocean to another continent," Chiang says. "A lot of us like to imagine that it's the same sort of thing as sailing from Europe to the New World, but it is radically different. Any species engaged in that kind of endeavor would have probably a completely different mindset than the ones that we are familiar with."

From reading the story, included in the anthology Stories of Your Life and Others, and from watching Arrival, it's obvious Chiang spent years studying linguists before assembling his story. As with his 1991 story "Understand" (about a man who receives a drug that increases his mental prowess), Chiang's characters have to rewire their brains in order to grasp ideas foreign to terrestrial beings. It's tempting to wonder if such a thing could happen outside the pages of his stories.

"There's nothing that would show up on an MRI or anything like that," he says. "There have been some studies that show that people who speak different languages, when they switch from one language to another, sometimes there are slight personality changes based on having to do with their cultural associations with those languages. There's nothing like a physical change in the brain that has been observed."

Friend or Foe

Chiang's aliens themselves don't fit the standard tropes that run through conventional sci-fi stories or films. For example, in Steven Spielberg's movies, the extraterrestrials can be friendly (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) or overtly hostile (War of the Worlds). Chiang and the makers of Arrival consistently made sure that Abbott and Costello, the heptapods, weren't as easy to classify.

"The heptapods in the story, their motives are largely impenetrable to us," Chiang says. "There's an idea known as the Fermi Paradox [after the late Italian physicist Enrico Fermi], which is the observation that the universe is old enough that intelligent life should have arisen and should have spread across the galaxy, but we don't see any of it.

"There are a lot of proposed explanations for why we don't see any of it, but one is that it's simply too dangerous to make any noise, to send signals into outer space to broadcast your presence. According to this presentation broadcasting the presence of intelligent life is the equivalent of putting up a big neon sign that says, 'Eat here!' You are inevitably going to attract the attention of some hostile species because in a galaxy of many species, you can't be certain there isn't going to be a hostile one. I certainly would like to believe that any species capable of interstellar travel would have gotten past the point of trying to destroy everyone that they see, but I guess I don't know if we can be certain of that."

Cloud 9, Not Plan 9

Since the early '90s, 15 of Chiang's stories have appeared in publications from Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine to Moni and even Nature. He has also won three Nebula Awards, including one for "Story of Your Life." Chiang's stories have appealed to readers who would normally avoid stories about life in other worlds, and it's rare to find a sci-fi film picking up Academy Award nominations because the field is often dismissed as a niche genre.

"There has always been serious writing in the field," Chiang says. "Hollywood has for many years been moving to a much more blockbuster oriented business model, so it has really become attracted to spectacle. It goes all the way back to the vastly greater success of Star Wars as compared to something like 2001: A Space Odyssey. There's this long history with science fiction films being associated with special effects and gigantic explosions.

"I hope the success of Arrival causes Hollywood to be more open to the possibility of midbudget, nonfranchise science fiction. I think that would be great. That would be the best possible outcome of Arrival's success."

Having penned less than a story a year hasn't forced Chiang to subsist on what college students charitably describe as food. Chiang has toiled as a technical writer (Microsoft has been one of his clients), which has enabled him to research and create his stories slowly and carefully. It's a wonderful guarantee for quality control.

"One of the things I'm drawn to about both is that I'm interested in explaining ideas. A really clear explanation is not just useful, it can be beautiful, as well," Chiang says. "Being able to convey an idea clearly to get them to understand something they couldn't understand before, that is something I am drawn to whether I am working as a technical writer -- that is obviously the goal of technical writing -- but it's something that I think science fiction can do."

MovieStyle on 02/17/2017